How to start a sound archive?

- ,

- , Raphael Kariuki

1. Walk about

One sunny midmorning, some day in 2013 or 14, Nairobi. Waiting to cross the road at one of the newly remade intersections with the fancy traffic lights (Chinese! Chinese!) is more distressing than usual. It’s the new lights. More accurately, it’s how the new lights sound. They beep loud and jarring, with a shrill, digital tone, adding to the impatient hootings and revvings. Nobody driving or walking seems sure what the signals mean or who they are for. Ten minutes down the road and walking steady, the racket is still in your ears and thoughts.

One twilit evening, 2013, Berlin. Waiting to cross a busy road not far from the famous TV Tower. Seems like rush hour, but does not feel like it. That’s when you notice it. The absence. If you closed your eyes, you would hear only the purr and whoosh of passing vehicles. You remark to your friend about it.

Another sunny midmorning about a year later, Nairobi. You are walking with a friend down a neighbourhood street that used to be lined with old houses from the 70s or 80s. Today it is clattering with jackhammers and chisels and all the familiar staccato of rapid construction. Passing by a rising residential block hidden behind gunny cladding, you wonder what used to be here. Hardly a year.

Nairobi, visiting a friend who lives in another new apartment block (reminds you of a great grey termite mound or nest of wasps) you notice the cacophony at the main entrance on the ground floor. The incessant beepings of the new KPLC pre-paid digital meters, like a noisy classroom when the teacher is out. A sound you are hearing more and more where there was only discreet neighbours before. You talk about these new sounds and a changing world.

2. Talk and procrastinate

You talk about sounds you no longer hear. The long-travelling low frequency rumble of an old-school KBS around the corner. The thump-thump of the sub-woofers in a number 23 several blocks away heading into the CBD from Westlands (out of sight but we all know where it is). You remember hearing the first ringtones in a matatu or on the streets. The fascinating novelty of an SMS notification. Nokia people. Kenyans and nostalgia. But what about history?

You start recording sounds around you. Some people use Zooms, some use their phones and even an expensive studio mic dangling out of a studio window, capturing the street below. You talk about possibilities. We could make something with these sounds. Nobody has any experience with sound art but it’s now a frequent topic. The conversation grows from what we can do with these sounds to what we can learn from them.

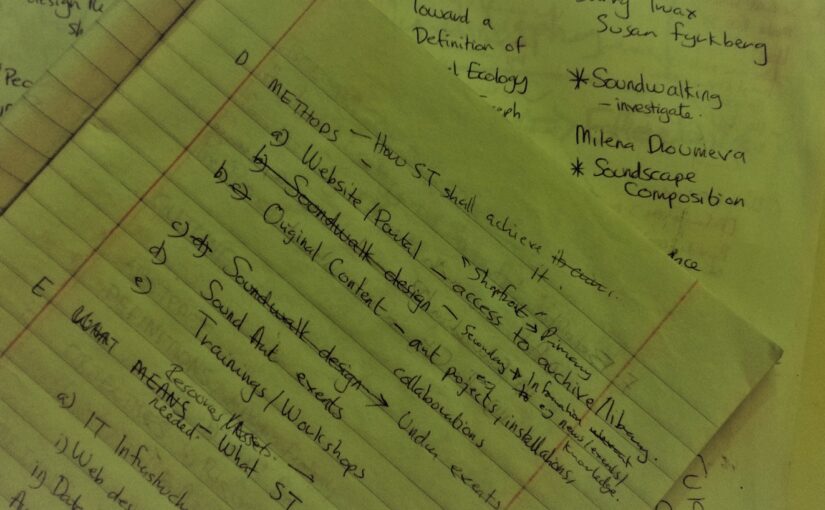

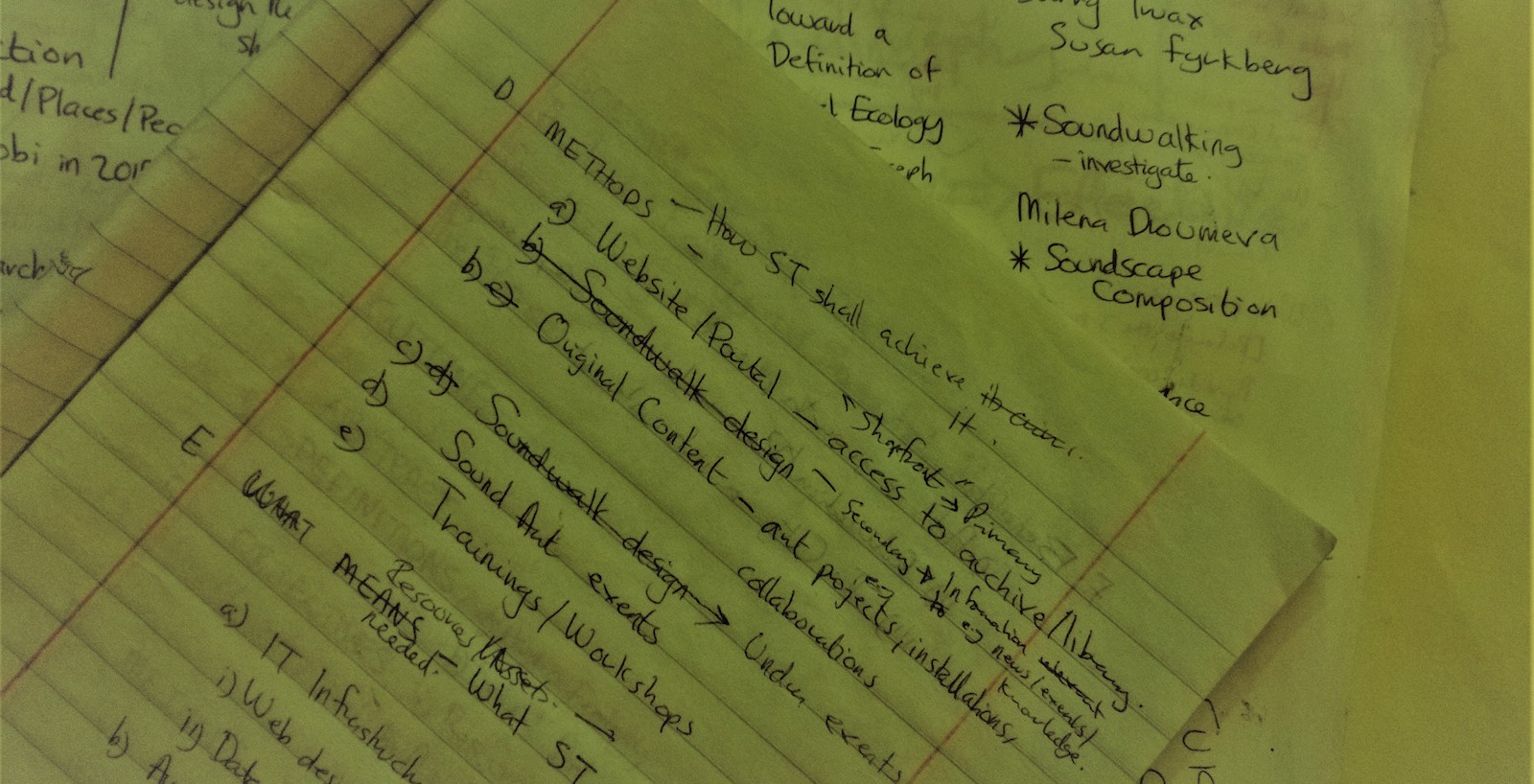

You sketch and doodle on your notebook(s). Share ideas by email. Plan to meet but when? Some people go to school others back to work and career and two or three years later we have all more or less disappeared. You add more notebooks to the heap, a decade’s worth of sketches and doodles. Your own archive – more like a personal landfill – of never ideas.

3. Seek help

Your friend who went back to school is back. Two years spent studying and practicing some of the things you used to talk about. In that meantime you have been dabbling in DIY sound and art. You revisit your conversations, digging in the notebooks. The idea of an aural record of Nairobi still makes sense. The idea of resourcing a nascent sound art scene feels timely. You have a friend who’s great with data tech. He is game and knows a guy who’s good with UI/UX. Work begins.

It is not a legit archive of the city if all it explores is the tiny street corner of your personal experience. The streets are many. Plus, the whole exercise is more fun when more people are involved. All this needs more people, time and money than you have on your own. So, reach out.

Approach friends and organizations willing and able to support. In addition to material and logistical support, you’ll get a huge boost of energy and goodwill. And you will make new friends along the way.

4. Launch and then party

Organize a sound exhibition and invite the world. Hand everyone a set of good headphones. They will love the immersiveness of the first recordings, because you used binaural microphones – realer than dolby. “Immersiveness” is a real word BTW.

Make a good party on the final day. Play music made from the archive.

5. After the party

-> “How To Maintain Your Sound Archive For Like A Century” – coming soon.

© 2020 SOUND OF NAIROBI