Hearing a Voice by Franziska Windisch

- ,

- , Sophia Bauer

Foreword

by Sophia Bauer, SON

Hello, today we are publishing an article by sound artist Franziska Windisch about voice.

This text, with the title Hearing a Voice, was first published in the booklet Equivocations, a collection of works by students of the Academy of Media Arts Cologne which I was part of and where I met Franziska for the first time.

Franziska is an artist and lecturer based in Brussels, Belgium. As an artist she works in many media (performances, text, composition, installation). Her work is concerned with notions of trace, sound and listening amongst others. As a student I have always enjoyed listening to her thoughts and impulses in seminars and lectures about sound. Check out her work here. And as SOUND OF NAIROBI we did the radio show #6 together with Franziska for the In Between Spaces project in 2020.

For me, voice has always been a conundrum and as well a starting point to think about sound in general: It is sound that transports meaning. It shows we can decode sound and use it to communicate. It is intrinsically individual but also meant to be public.

As a Non-Native-Nairobian and -Kenyan I do not understand every language and person in the city. I think what I have learnt by not understanding the words is listening to the voice, the subtleties and shifts in tone, the ‘grains’ and therefore maybe being able to decode the other person’s feelings and emotions and then have a conversation.

Nairobi is a place of many languages ( 42+ ). And so I am guessing a lot of people in the city have had my experience and are used to listening to others in different and multiple ways. Sometimes I feel the city has an openness to misunderstanding and people are often willing to engage with each other to understand each other – can a ‘functioning’ community be build on misunderstanding? This is an interesting thought to me.

Nairobi is also a place of many many voices. Some of them are unheard but powerful if listened to.

Hearing a Voice

by Franziska Windisch

Some years ago I explored the peripheries of a middle eastern city. I walked along a busy highway at the entrance of the city when I suddenly heard a screaming voice. Somebody screamed against the heavy traffic noise, against the heat and dust in a rhythmical sequence that was repeated again and again with pertinence. It left me wondering: was it a prayer, an expression of grief or anger, a ritual? I couldn’t even tell if that voice belonged to a man or a woman, nor did I understand a word. But there was something deeply existential in this exclamation, as if this person wanted to drown out the trucks and cars – a hopeless endeavour. In the same time I had the impression that the heavy noise of the highway was like a sonic shell that opened up a space of anonymity, a sort of protection that evoked a sense of privacy in this inhospitable environment and that made me almost feel like an intruder. Every vocal sound seeks contact, might it be gods, ghosts, trucks, lovers or strangers – who did this voice address?

The voice as a single phenomenon is an enigma. We can never fully grasp where it begins and where it ends, what it expresses, what it conceals and who it belongs to. We recognize its uniqueness and at the same time we are aware of the countless imitations it is shaped and composed of.

A voice always refers to a body. Through using ones voice the body becomes resonant and vibrates and it seeks to set others into resonance. The voice reaches out for others to share and transmit affects, to reassure oneself of the presence of others, to sound and resound with a group of beings. This is applies to a vast range of species – cicadas, blackbirds, wolfs, humans all use their voice to organize their spatio-temporal and social ties towards one another. In this context it is also crucial that voices can be differentiated as slightly distinct. In humans the oral cavity with teeth and tongue, the larynx and the vocal chords, in short the whole body of the speaker produce entirely unique sounding voices, which also explains why the voice is deeply interlinked with notions of identity and gender. But the corporeal aspects of a voice are not solely something given and unchangeable, but an area that is subject to the expressive intentions of the speaker. Vocal gestures, tonalities and textures are continuously appropriated, modified and applied to specifics contexts. After all forms of vocalizations (including learning to speak) rely on imitation and play, become habitually formed and deliberately constructed.

One essay that is concerned with the sonorous qualities in human speech is Roland Barthes’ “The Grain of the Voice”. The embodied voice appears to be heard with its “grain”, a term that seeks to characterize the materiality within vocal gestures, as “a site where a tongue encounters a voice”(1). Hearing a voice is an encounter, an encounter that begins and takes place to a great extent beyond the realm of the linguistic. “Listening to the voice inaugurates the relation to the Other: the voice by which we recognize others indicates to us their way of being, their joy or their pain, their condition; it bears an image of their body and, beyond, a whole psychology”(2).

What resonates in these texts, that locate the voice somewhere between a metaphorical and physical body, is a centuries old internal split. The voice has often been theorized as a field where two independent orders are present: the order of language and the order of sound, a dichotomy that originates from the classical era. When the ancient Greeks used the word phoné they meant the voice of humans and animals, as any other audible sound(3). Logos on the other hand was reserved for the speech of humans, for the voice that transmits semantic content and communicates rational ideas, the voice that signifies – phone semantike. As a consequence the vocal becomes a mere acoustic carrier of meaning, without “any value that would be independent of the semantic”(4) and is therefore seen as subordinate in relation to logos, a term that in the metaphysical tradition stands not only for “discourse” but finally also for a (voiceless) “reason”(5).

Oral culture has been for a long time primarily examined from a logocentric perspective, as a constitutive element for the construction of state, law, science and education. Think for instance of practices in court like judicial decisions and witness testimony, of contracts becoming only legally valid when read out loud, of defending academic theses, of debates and votes in parliaments (6). More recent studies explore the bodily aspects of the voice (like Brandon Labelle’s Lexicon of the Mouth) that focuses on the materiality and the performativity of vocal gestures.

The question that still remains here, […] how can we think the voice as a complex that holds account of its manifold divergent aspects without falling into a centuries old dualism, but rather actively and experimentally exploring the potential that lies in its internal multiplicity?

One approach could be to open it up to the act of listening, to see the voice not as a singular phenomenon but as a process that appears only in relation to a listening. Hearing a voice calls for an answer, for reciprocity. Hearing a voice means to acknowledge the relation that is established by ones listening, an attention that becomes acoustical tension between speakers an listeners.(7) This interpersonal territory can have many facets, it holds a vast range of interlinked sensual experiences and meaning making processes. Listening doe snot really separate sharply between different categories but is rather a fractured multiplicity in itself, that constantly differentiates and shifts its concentration between the interpretation of signs and sounds, distances, timings and memories and therefore actively produces what is communicated. To consider the perception of sounds and the production of signs as an entangled process, where the sensible is interwoven with the intelligible lies also at the heart of Jean Luc Nancy’s well known essay “Listening” that thinks with the phenomenon of resonance: “Meaning and sound share the space of a referral [renvoi]”(8). The discursive – sensual space of referral that opens up through listening is not only regarded as a space between subjects, but also a resonating internal space that constitutes the very Self. Hearing a voice therefore is a simultaneous correspondence to the Other and to the Self (as alterity).

Here we can ask: who does the voice belong to? Isn’t it always calling out for the Other to be heard, always already outside of oneself? Only recognized within one’s listening? Hearing a voice seems to be a process on the borderline between oneself and the other. It is a phenomenon that can’t be located. Created by the manifold (feedback) loops in which we enter into relation with ourselves and the world, it is an aesthetic – semiotic process that is always embodied: “no voice is purely semantic. The body speaks in more ambiguous ways and my listening body answers this ambiguity”(9).

While wandering along the highway years ago I realized that any vocal sound, even if hidden or transmitted, is situated in an environment and that an environment is ultimately a shared space. I still keep wondering what “shared” in this context could mean, as my listening lacked understanding of language and context. “But I remember clearly that beyond all those uncertainties (or because of them?) this voice was to me a powerful and direct expression of someones existence. A voice, because it came probably from a place of being unheard, became powerful within and for itself.

1 Barthes, Roland. Image Music Text. New York: Hill and Wang, 1977, p. 255

2 Barthes, Roland. Listening from Responsibility of Forms p. 254

3 Cavarero, Adriana. For more than one voice, p. 19

4 Cavarero, Adriana. For more than one voice, p. 35

5 Ebd. 33

6 Dolar, Mladen. A Voice and Nothing More, The MIT Press 2006, p. 177 ff

7 LaBelle, Brandon. Lecture on an Acoustics of Sharing p. 20

8 Nancy, J.-L. Listening p. 8

9 Voegelin, Salomé.Listening to Noise and Silence p. 37

References:

Barthes, Roland. Image Music Text. New York: Hill and Wang, 1977

Barthes, Roland. Listening from Responsibility of Forms

Cavarero, Adriana. For more than one voice, Toward a Philosophy of Vocal Expression, Stanford University Press 2005

Dolar, Mladen. A Voice and Nothing More, The MIT Press 2006

LaBelle, Brandon. Lecture on an Acoustics of Sharing 20

Voegelin, Salomé.Listening to Noise and Silence, Towards a Philosophy of Sound Art, Continuum 2010

Nancy, J.-L. Listening (Charlotte Mandell, Trans.). New York: Fordham University Press. 2007

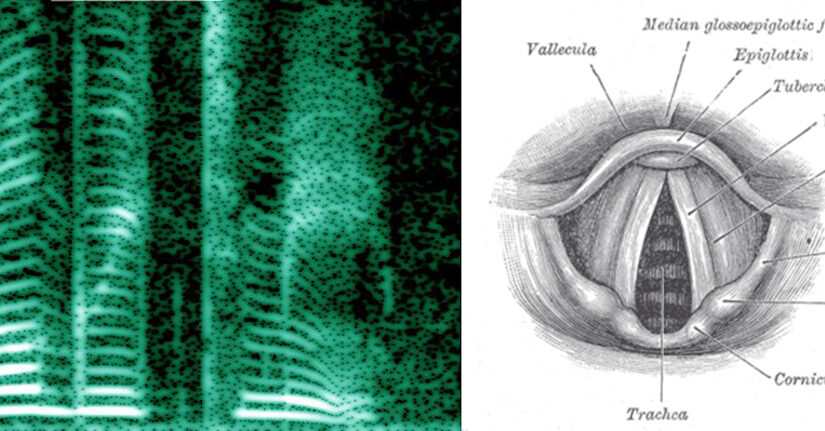

Photos:

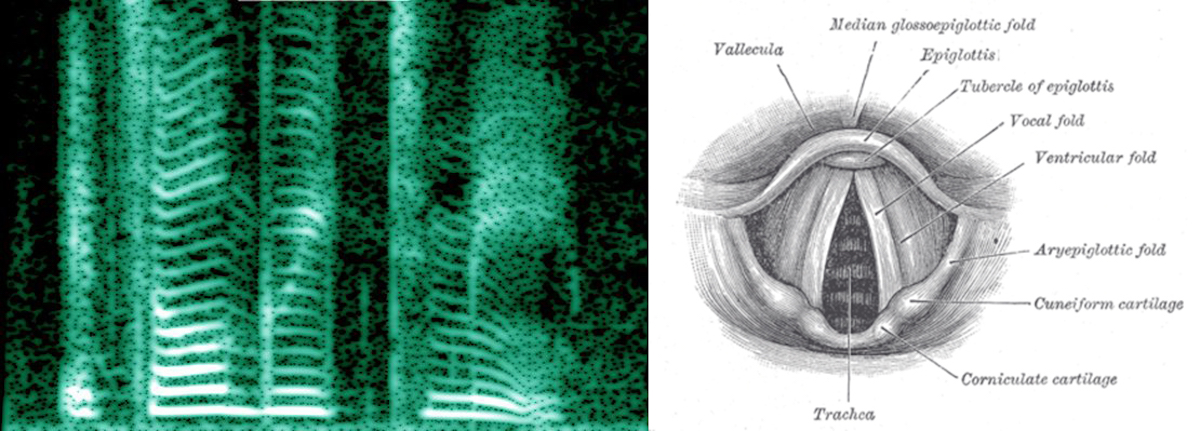

left: The spectrogram of the human voice. (source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Human_voice)

right: A labeled anatomical diagram of the vocal folds or cords. (source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Human_voice)

© 2020 SOUND OF NAIROBI